MarkBeck.org

Welcome to an information page focused on what I believe is a critical problem: Planning safer communities in the face of natural, climatic, geologic and man-made hazard events--more specifically, how to keep us all "out of harm's way." The Urban Land Institute defines "Building resilience" as "identifying and investing in places and infrastructure that are the most likely to endure." That's the answer in a nutshell. So please read on! I welcome your feedback!

Photos

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

A Visit to Welch

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Welch, WV

|

| Photo by TripAdvisor |

In a post last week, I highlighted the plight of the town of Welch, WV and its precarious location beside the confluence of the Tug and Elkhorn Rivers, both with a history of flooding. Sandwiched on tiny slivers of land between the rivers and tall wooded mountains that snake through southwestern West Virginia, there isn’t much room for water and people to coexist when the rains fall.

Welch was, for the first half of the 20th Century, a prosperous coal town. Mining meant jobs, and local coal fed the appetites of nearby steel mills and beyond. Welch claimed itself “The Heart of the Nation’s Coal Bin.” After the end of WWII, much changed. By the 1960s, automation reduced the demand for mining labor, smaller steel mills closed, and the population of Welch (and McDowell County) dwindled. One history adds this observation:

When presidential candidate John F. Kennedy visited Welch by automobile caravan in 1960, he saw a city whose businesses were struggling due to a growing poverty rate throughout the county. What Kennedy learned here during his campaign for the 1960 West Virginia primary was believed to be the basis of the aid brought to the Appalachian region by the Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson administrations. During a speech in Canton, Ohio on September 27, 1960, he stated "McDowell County mines more coal than it ever has in its history, probably more coal than any county in the United States and yet there are more people getting surplus food packages in McDowell County than any county in the United States. The reason is that machines are doing the jobs of men, and we have not been able to find jobs for those men."

The first recipients of modern era food stamps were the Chloe and Alderson Muncy family of Paynesville, McDowell County. Their household included fifteen persons. On May 29, 1961, in the City of Welch, as a crowd of reporters witnessed the proceedings, Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman delivered $95 of federal food stamps to Mr. and Mrs. Muncy. This was the first issuance of federal food stamps under the Kennedy Administration, and it was the beginning of a rapidly expanding program of federal assistance that would be legislated in the "War on Poverty".

In the 1960s and 1970s, McDowell County coal continued to be a major source of fuel for the steel and electric power generation industries. As United States steel production declined, however, McDowell County suffered further losses. In 1986, the closure of the US Steel mines in nearby Gary led to an immediate loss of more than 1,200 jobs. In the following year alone, personal income in McDowell County decreased dramatically by two-thirds. Real estate values also plummeted. Miners were forced to abandon their homes in search for new beginnings in other regions of the country.

The Welch of the 21st Century is but a remnant of its former self, yet those rugged, hard-working citizens who remain in the town hold tenaciously to their homes and community with pride. They watch out for each other too—just like the statement in my prior post by McDowell County Commissioner Michael Brooks who said the people of his county will step into harm’s way for their neighbors.

So it must be difficult for some to accept that, to avoid the incessant danger and threat of rising flood waters, they’ll have to leave. Agencies like the Natural Resources Conservation Service offer buyout opportunities with incentives to encourage those in the most flood-prone areas to seek a new life elsewhere. Land purchased through this program is restored to flood plain conditions and development is banned.

But not everyone can simply start over elsewhere. Something must be done to help those who remain. There are solutions. And the solutions offer hope, but not without controversy. Just four days ago a local news outlet shared the following:

McDowell County Commissioner Michael Brooks is frustrated. He believes one of the biggest issues is a lack of proper stream maintenance in the county.

“There needs to be a massive effort throughout McDowell County and southern West Virginia to dredge and clean our streams. They’re completely full and many of our streams are nearly at road level, those that weren’t after this are now. That is a major, major issue,” said Brooks in an appearance on MetroNews “Talkline” which was live in Welch Thursday.

Brooks isn’t alone. Many have talked about the need to scour out the bottom of waterways like Elkhorn Creek and the upper stretches of the Tug Fork River along with tributaries which overflowed and caused major damage and destruction. Brooks said it doesn’t even take a major flood to push water into a roadway in many cases.

But there are always debates and roadblocks to dredging.

Money is always a factor when considering the cost of the work. Some often argue the cost of rebuilding is far less than the cost of mitigation.

But the bigger obstacle to dredging is environmental protection. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies typically throw up roadblocks to dredging to protect endangered species and the destruction of their habitat. The area’s watershed is home to several rare types of crayfish and the Candy Darter, all of which are considered species on the brink.

Brooks said his concern is McDowell County’s human population is on the brink.

“We can restock crawdads and we can restock fish, but when people leave these communities they never come back. That is unfortunately what we have faced here in McDowell County. When the population goes from 30 to 40 thousand people down to 18 thousand or so, people are tired,” he explained.

Brooks added after every flood the county has endured the population took a hit. People continue to leave his county in droves, many of them run off by an inability to protect their homes from rising water and an unwillingness to risk having to endure it again.

“In my opinion, respectfully, there’s a lot of people making these decisions that affect the lives of people like our folks here in southern West Virginia who live in a subdivision somewhere and never have those issues. We need some kind of a panel of folks who have lived this continually throughout their lives to demonstrate the significance,” said Brooks.

There are always trade-offs when it comes to nature and development, and it may be possible to create pathways for floodwaters and protect vulnerable structures. In fact there must be a way. But that’s a topic for another post.

In the meantime, please enjoy this video introduction to the people of Welch and McDowell County.

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

A Bridge to... SOMEWHERE!

McDowell County, West Virginia has consistently been among the poorest counties in the state and the country. In 2024, the county’s median household income was $27,682, which is more than 40% below the state median, according to the US Census Bureau. And yet the county suffers from a long history of devastating floods—three in the last 25 years that caused death and destruction. The winter storm that wreaked havoc over the central and eastern part of the country earlier this month was the third. The local news reported that:

At least one fatality has been confirmed, and there are still people unaccounted for. The Tug Fork River reached historic levels, and rainfall compounded on the flooding with over a month’s worth of rain in just two days. Lives, homes, businesses, and critical infrastructure have been severely impacted.

Over the weekend, relentless rainfall turned roads into rivers, trapping residents and destroying property. In Welch, floodwaters surged through the town much of Saturday and into the evening. Vehicles were overturned, roads and sidewalks were caked in thick mud, and countless businesses and homes fell victim to the floodwaters.

“[It was] carnage to be honest with you. Some people lost everything. Some people lost their lives. It’s horrible, and I don’t know what to say. It actually tugs my heart talking about it.” Sheriff James Muncy Jr. said on Sunday.

Waterlogged streets, collapsed embankments, and desperate rescue efforts paint a forbidding picture of the situation and show the scale of the devastation…

The Tug Fork River crested at 22.1 feet on Saturday around 10 PM, tying 2002 for the highest levels recorded in history. The rush of water left the streets of Welch caked in mud, flooded houses and businesses, and made countless roads impassable. The infrastructure damage has only compounded the issue of safe roadways.

The following statement, however, says it all about the people of McDowell County.

Despite the damage, the resilience of McDowell County residents is undeniable.

“You know, we have some of the best people in the country here in McDowell County. And we’ve got folks that have basically—they’ve really placed themselves in harm’s way to try to look out for their neighbors and try to do all that we can,” Commissioner Brooks said.

The County suffers when the rains hit and the rivers swell, and there may not seem like much can be done; but there are infrastructure improvements that, if funded, would make a world of difference. Organizations like the NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) have purchased properties in flood-prone areas, such as the Elkhorn Creek/Tug Fork River Watershed. Residents in those areas are being offered an opportunity to relocate. And of course, walls, raising foundations, and other diversion techniques would help.

The town of Welch has a particular problem with an underpass beneath the railroad on the main road leading to town. It’s too short for some traffic and a lower section that provides access to higher vehicles floods during storms. Even worse, the hospital and the town are on opposite sides of this dangerous underpass. In a local TV newscast, Welch Mayor McBride said he believes the citizens of Welch deserve a new bridge that is not such a dangerous hazard.

“It’s a way of life, a quality of life that just has to be done. It’s time. It should have been done a long time ago, but I don’t want somebody twenty years from now saying it should’ve been done. We campaign hard for it. The governor has been very accessible to it… We’re not gonna give up no matter. As long as I’m here, they’re gonna hear from me screaming about a bridge.”

One simple remedy would make a huge difference to this town and others who must pass through it.

To help the people of McDowell County please consider

donating to the charities listed here.

And here.

And for a heartwarming story of one hero of McDowell County, please watch this brief video. And consider helping Sharon's cause here.

Monday, December 9, 2024

Wildfire Infographic

Wednesday, January 24, 2024

Unnatural Disasters Are The Most Dangerous

When it comes to establishing policies and practices that promote resilient communities, there is much attention given to climate-related events. In fact, the United Nations' Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, doesn't even mention earthquakes (or tsunami or volcanic eruption) within its pages. As this blog so frequently points out, however, geologic hazards (and related events) take as many lives as climate disasters do. Adapting to both must be our focus, regardless of what actions we may take on the climate side to adopt mitigating practices like reducing energy and carbon emissions.

Curious, I began investigating historical statistics regarding the disasters that have killed the most human beings, thinking that we should always prioritize measures to thwart those events at the top of our adaptation policy list. It didn't take long to discover something quite horrific. The most loss of life for any known historic (non-war, non-pandemic-related) disaster occurred in the very recent (relatively speaking) past--partially within my own lifetime, in fact.

First, I ran across this fascinating graphic. It's a very large image (in its original form, here), but a piece of it is depicted below:

See the largest "bubble?" It turns out that the largest loss of life in a known disaster occurred during the Great Chinese Famine of 1957-62. Many tend to remove "famine" and "pandemic" from the list of disaster mortality statistics, as they would war deaths. But I appreciated this article addressing it as they did--particularly given that the famine has, at least in part, "natural" origins. Like so many natural events that turn into "disasters" due to human activity, however, this one swelled out of control and destroyed (estimated) 23 million to as many as 55 million lives. And the reasons for the exacerbation, though complicated and highly convoluted, stem primarily from the policies and actions of the country's Government at the time. Accounts of what happened and why, range from the scientific to the political to the emotional. The accounts (particularly the one linked as "emotional") are sobering.

A recurring theme among these historical accounts is a lack of transparency and a seemingly deliberate ignorance of reality that prevents leaders from seeing, let alone understanding, the problems and potential solutions. I won't dwell on the details, but I will share the following from the article from AsianStudies.org linked above:

"According to one study, China experienced some 1,828 major famines in its long history, but what distinguishes the Great Leap Forward from its predecessors are its cause, massive scope, and ongoing concealment. In his recent study of famine, Cormac Ó Gráda suggests that, historically, famines emerged from natural phenomena, sometimes exacerbated by human activity. Modern famines, on the other hand, stem from human factors such as war or ideology exacerbated by natural conditions."

Such was the case in the 1950s-60s China. Like I wrote here many times during the recent COVID-19 Pandemic, building disaster-resistant communities is so much more than just moving (or raising) infrastructure. It's as much about people. How we interact, how we treat each other, and how we plan ahead for potential problems is critical to helping preserve our lives and livelihoods. We need to demand a responsive government with an open mind to keep the best interests of their citizens in mind.

-----------

To assist the hungry today, please consider donating to a charity like this one.

Wednesday, September 20, 2023

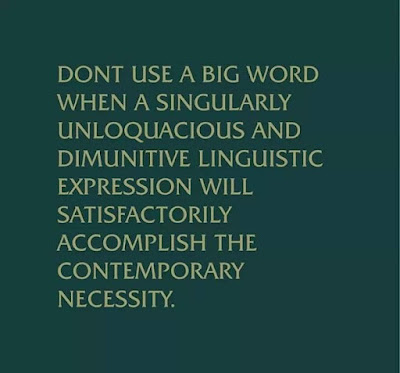

Telling It Like It Is

Please allow me a brief personal diversion into a topic that I feel quite strongly about. I don't mean to disparage any particular academic or researcher, so I won't divulge specifically the source of these sentences, but please read the following that crossed my desk in a scientific article recently:

Unsafe conditions (exposure to hazards) are shaped through a series of disaster risk drivers generated from processes, priorities, resource allocation and production–consumption patterns that result from different socio-economic development models. In essence, disaster risk drivers emanate from the ways the basic goals and parameters for growth and societal definitions of development are established and implemented.

I believe what the authors were saying could have been more simply stated, perhaps like this:

Because social and economic conditions vary by community, we expect to see each have their own unique priorities, different patterns of production and consumption, goals for resource allocation, and patterns of physical growth and development. These characteristics, in turn, contribute to unique exposures to hazards or risks that must be addressed.

Without having completed the original research, I'm only interpreting the writers' intent. And as you'll see in reading entries in this blog I'm as guilty as anyone for resorting to imprecise, jargon-clouded language. But my point is that we should all try to find ways to say what's needed in a manner that is more easily understood by all.

"The Plain Writing Act of 2010 was signed on October 13, 2010. The law requires that federal agencies use clear government communication that the public can understand and use." The Federal government's web site addressing this law includes a number of guides, helpful hints, and even some humorous examples to illustrate the need for the use of plain language in all government documents and records.

When it comes to the topic of hazard mitigation and resiliency in communities, where citizens and government officials need to be "on the same page" with the scientists and engineers, it goes well beyond simple "best practice." When addressing natural hazards and preparing for potential impact on human activities, clear communication is absolutely critical and can save lives.

It's not just external (community) communication either. There are real benefits for scientists and researchers themselves to adopt a more "plain language" approach for all technical writing--even among peers. Lily Whiteman, a contributor to the Washington Post and a senior writer for the National Science Foundation, shares the following:

Plain language is one of our best tools for improving scientific literacy and encouraging wise decision-making by the public on science-based issues. It is important for scientists to use plain language not only to reach the public; but also to reach one another. Indeed, scientific information conveyed in plain language invariable reaches bigger scientific audiences than information conveyed in technical language. Evidence of this includes the following:

A recent study showed that medical articles reported in The New England Journal of Medicine and then reported in The New York Times receive about 73 percent more citations in medical reports than do articles not reported in The New York Times.

The Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine is a nationally successful journal with the best readership growth trend and advertising growth trend in its market. But The Cleveland Clinic Journal wasn’t always so successful. Until the mid-1990s, it was a forgettable, low circulation journal. How did the editors of The Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine dramatically increase their readership? By replacing their journal’s dense, long-winded, jargon-filled style with an alternative style that incorporates the principles of plain language.

The quote, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication,” is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci.

I couldn't have said it better. Or more clearly.

Wednesday, September 13, 2023

"Baltimore will take care of its own, thank you"

The year was 1904.

What began as a small fire in the basement of the Hurst Building in Baltimore soon spread to nearby buildings and, fanned by high winds and dry conditions, soon became a legendary conflagration that wiped out or severely damaged an estimated 2,500 buildings spanning dozens of city blocks. For over a century, it was considered the third worst urban fire in US history (behind the Great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 and the Great Chicago Fire of 1871). Damage was estimated at over $4 billion in today's dollars and 35,000 people were left unemployed.

A descendant of one of the fire fighters who documented the fire's cause, progress, and legacy, posted a well-researched history and numerous photos (including those on this page) HERE. An eyewitness wrote:

Tongue fails, pen is inadequate, mind refuses to comprehend the extent of the disaster,but, some idea of the size of the district which has been swept may be gathered when it is stated that it includes more than 175 acres of ground—all of it in the heart of the business section.

Miraculously, no deaths were officially reported as a result of the fire, though evidence has been uncovered that there were at least one or two reports of loss of life. Local leaders addressed the emergency in a holistic way, utilizing a large number of firefighters from neighboring states and municipalities.

In addition to firefighters, outside police officers, as well as the Maryland National Guard and the Naval Brigade, were utilized during the fire to maintain order and protect the city. Police and soldiers not only kept looters away, but also prevented civilians from inadvertently interfering with firefighting efforts. The Naval Brigade secured the waterfront and waterways to keep spectators away. Officers from Philadelphia and New York also assisted the City Police Department.

BALTIMORE: THE AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

The most interesting parts of this story are the reasons for the dramatic spreading of the flames and the resilience the City and its leaders demonstrated throughout the ordeal and afterward. So why did the fire spread so quickly? Even given the poor weather that exacerbated the spread of the flames, the reasons were the same as those commonly heard after other urban fires at the time, and for many similar fires in less developed metropolises today:

Close living quarters; lax, unenforced, or non-existent building codes; and a widespread dearth of firefighting services were all contributing factors to the frequency and extent of urban fires. The rapid expansion of American cities during the nineteenth century also contributed to the danger.

In addition, firefighting practices and equipment were largely un-standardized, with each city having its own system. As time passed, these cities invested more in the systems that they already had, increasing the costs of any conversion. In addition, early equipment was often patented by its manufacturer. By 1903 (for instance), over 600 sizes and variations of fire hose couplings existed in the United States. (The correction of this problem was one of the most valuable outcomes of this expensive tragedy.)

For Baltimore, the fire was a turning point in the development of building codes and standards. Shortly after the fire, the local paper recorded a statement by the City's Mayor Robert McLane and his outright refusal to accept outside assistance:

"To suppose that the spirit of our people will not rise to the occasion is to suppose that our people are not genuine Americans. We shall make the fire of 1904 a landmark not of decline but of progress... As head of this municipality, I cannot help but feel gratified by the sympathy and the offers of practical assistance which have been tendered to us. To them I have in general terms replied, 'Baltimore will take care of its own, thank you.'"

And they did. "Baltimore finally adopted a city building code after seventeen nights of hearings and multiple City Council reviews. The city's downtown 'Burnt District' was rebuilt using more fireproof materials, such as granite pavers. Public pressure, coupled with demands of companies insuring the newly re-built buildings, spurred the effort."

Just two years after the blaze, the Baltimore Sun reported that "the city had risen from the ashes and that one of the great disasters of modern time had been converted into a blessing." How did that happen? An introduction to a collection of materials about the fire on file Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library includes the following explanation:

Baltimore City officials and the State of Maryland were quick to respond in the aftermath of the fire. The Citizens' Relief Committee (CRC) and BDC were each established by an act of the Maryland General Assembly and put at the disposal of Mayor Robert M. McLane. The CRC was given a fund of $250,000 to disburse for the immediate relief of those individual citizens who had lost property in the fire. Financial aid came in from around the country as well.

It is testament to the resilience of Baltimoreans that only a mere $23,000 was spent. The BDC set to work creating and implementing plans to clear away debris and rubble and to clear and widen streets and rebuild and open public spaces. It took three years to do it, but they played a significant role in helping Baltimore get back on its feet to thrive and flourish as a bustling metropolis once more.

FAST FORWARD TO 2023

Lahaina, Maui in the State of Hawaii.

Lahaina, a former whaling town that evolved into a major tourist attraction, was once the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii and the historic district was placed on the National Register in 1962. But on August 8th, a brush fire was reported east of the historic city. A variety of sources summarized HERE, continue the story:

The wildfire rapidly grew in both size and intensity. Wind gusts pushed the flames through the northeastern region of the community, where dense neighborhoods were. Hundreds of homes burned in a matter of minutes, and residents identifying the danger attempted to flee in vehicles while surrounded by flames. As time progressed, the fire moved southwest and downslope towards the Pacific coast and Kahoma neighborhood. Firefighters were repeatedly stymied in their attempts to defend structures by failing water pressure in fire hydrants; as the melting PVC pipes in burning homes leaked, the network lost pressure despite the presence of working backup generators.

Residents rushed to flee the old town, with its tinder-ready wooden structures. Some ran into the ocean to escape the flames. But the evacuation was delayed and slow.

Officials said that civil defense sirens were not activated during the fire even though Hawaii has the world's largest integrated outdoor siren warning system, with over 80 sirens on Maui alone meant to be used in cases of natural disasters. Several residents later told journalists that they had received no warning and did not know what was happening until they encountered smoke or flames. There had been no power or communications in Lahaina for much of the day, and authorities issued a confusing series of social media alerts which reached a small audience.

To-date, the death toll stands at 115 persons. Estimates of damage range, so far, between $3.2 and $5.5 billion. Last week, Governor Josh Green delivered an address to mark the date one month "since flames tore through historic Lahaina town, leaving at least 115 people dead and razing more than 2,200 structures. In addition to the unthinkable death toll, the fire has devastated Maui’s economy and left 7,500 displaced. In an address Friday from his ceremonial room, Green said that Hawaii continues to grieve with families who have lost loved ones. He also offered an update on the number of missing, saying that number now stands at 66 — down from 385 last week and more than 3,000 originally."

|

| https://www.cnn.com/us/live-news/maui-wildfires-08-09-23/ |

Watching media accounts of the Maui fires as they raged, I couldn't help but compare and contrast this situation to that of Baltimore in 1904--albeit in a very different environment. The story was familiar. There were physical contributing factors (weather) and a population center occupying structures made of primarily flammable materials. There were local leaders struggling to deal with an ongoing emergency and then trying to settle post-fire investigations and finger pointing. Unlike Baltimore, there was little available help from surrounding communities and states as the fire raged. The Federal government stepped in, but well after the worst had passed.

My conclusion is a simple one, but one I hope to see play out well for the historic town, the state and for the survivors of the tragedy. Local and state leaders are at a crossroads, not unlike Baltimore in 1904. Whether they accept responsibility and lead their own recovery like Baltimore's leaders did, or whether politics continues to tie their hands and delay the healing of their community, is up to them.

Ultimately, however, like the Baltimore Sun reported 115 years ago, I hope that news media in Hawaii will one day soon be reporting that "the city has risen from the ashes and that one of the great disasters of modern time had been converted into a blessing."

NOTES:

For a fascinating presentation on the history of fires (including Baltimore) and the changes in fire codes they brought about, click here.

The youthful mayor of Baltimore during the fire died shortly after the fire, under mysterious circumstances. Story here.